Whiplash

Whiplash can be one of the most challenging musculoskeletal conditions to treat. It can be challenging for both the patient and the therapist. If the correct medical and physical interventions are utilised however, a patient’s recovery can be greatly improved.

Initial intervention of the cervical whiplash patient

Patients present to physiotherapy at varying times after the initial injury. Some will come the very day they have been involved in a vehicle accident whilst others will arrive many years after the event when they are struggling to deal with the remnant physical restrictions or pain.

Patients present to physiotherapy at varying times after the initial injury. Some will come the very day they have been involved in a vehicle accident whilst others will arrive many years after the event when they are struggling to deal with the remnant physical restrictions or pain.

The best prognosis, irrespective of the type or severity of the whiplash, invariably comes when patients present to their general practitioners in the first 24 hours after the initial trauma. Patients will not only be in pain, but are often dealing with the shock of having been involved in a car accident. They are concerned not only about their physical well-being but also that of their family – will they be able to continue to work, how will the family function without the car, what is their long term outlook? For this reason, whiplash patients, having so much on their mind, are often less committed to their rehabilitation. They are often healthy individuals who have never dealt with severe pain and life-style restriction before and in many cases become distressed very quickly as they come to terms with the gravity of their situation.

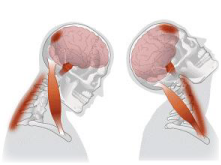

Beyond reassurance and support of such patients, the most crucial intervention in these first few days is to prevent or limit the ‘pain cycle’ – the onset of inflammatory mediated pain that spirals into worsening muscular spasm, restriction and impaired tissue healing or scarring. Prophylactic analgesia as well as anti-inflammatory interventions is crucial in patients, even those with minimal symptoms initially. (Often patients seen in the first 24 hours do not present with many symptoms – these can take over a week to fully develop). Concern has been raised about the reduced clotting effect of non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAID’s) and whether these are warranted in the first few days. As bleeding within damaged tissues following whiplash is seldom present to any large degree, such concerns, in most cases, are without merit.

Likewise, what tissue damage exists around the cervical spine is far too deep for either ice or heat applications to effect secondary tissue damage. Heat, in the form of hot showers, hot pack applications and even covering the neck region warmly when dressing, does limit superficial muscular spasm and for this reason, is recommended to nearly all whiplash patients from day one. The exception to this rule is when the head, neck or upper trunk has directly impacted other objects during the collision and superficial contusions and bruising have resulted.

Unless muscle spasm is severe and debilitating, or in cases where the underlying damage is unclear, (eg potential spinal fractures, spinal shock or cord irritation), cervical collars are generally not prescribed routinely. A patient’s compliance with wearing these is variable at best and due to the diverse nature of whiplash injuries, consistent recommendations in the literature are difficult to find. If cervical collars are prescribed, it is vital that they are correctly fitted, used only for the short term (generally no more than a week) and periods without the brace where controlled movements and ranging exercises can occur, are prescribed for the patient.

Physiotherapy assessment of the cervical whiplash patient

During the initial consultation, a physiotherapist will assess the nature and severity of the trauma that has occurred. This of course plays a crucial role in formulating a rehabilitation plan but perhaps more importantly, helps provide a clearer picture of the long term prognosis and implications of their symptoms. These first few consultations focus on educating the patient on what to expect in the coming weeks and months. When patients are not fully aware of exactly what has occurred, what treatment will transpire and the precise role they play in their own recovery, the outlook is grim indeed.

One must assess the speed and nature of the motor vehicle accident – was it a rear or side impact, were seat belts worn, was the patient able to pre-empt impact, was the head turned at the time of collision and what type of cars were involved. Perhaps as important, as this becomes a stickling point with insurance companies and lawyers as costs escalate, is what pre-existing conditions of the neck and upper limb existed at the time. For this reason, even basic x-ray imaging is helpful in the initial stages. Beyond ruling out bony insult, pre-existing injury and perhaps upper cervical instabilities, it does little to help govern intervention or determine prognosis in these early stages.

One must assess the speed and nature of the motor vehicle accident – was it a rear or side impact, were seat belts worn, was the patient able to pre-empt impact, was the head turned at the time of collision and what type of cars were involved. Perhaps as important, as this becomes a stickling point with insurance companies and lawyers as costs escalate, is what pre-existing conditions of the neck and upper limb existed at the time. For this reason, even basic x-ray imaging is helpful in the initial stages. Beyond ruling out bony insult, pre-existing injury and perhaps upper cervical instabilities, it does little to help govern intervention or determine prognosis in these early stages.

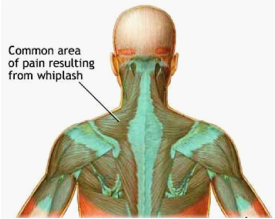

Patients are questioned on their primary (main presenting) and secondary symptoms – these may include headaches, forgetfulness, lethargy, confusion and even aggression. Physically they are assessed for cervical, thoracic, chest and upper limb movement as well as tenderness and muscular spasm in this region.

Physiological range of movement is assessed – flexion, extension, cervical rotation and lateral flexion. This is often done in a relaxed sitting or standing posture as well as with the shoulders actively elevated. This helps to ascertain if there is limited movement as a result of joint immobility or muscular tightness.

Vertebral artery questioning and assessment is also performed routinely in whiplash patients. This specific assessment must legally be carried out on all patients whose pain has an upper cervical origin or if high velocity thrust manipulations are to be carried out above C3. Even if manipulative techniques are not on the agenda, vertebral artery assessment is a quick and responsible management protocol for whiplash patients.

The therapist will then assess ‘joint specific’ movements in the same directions as described above. This is done by feeling each vertebral segment individually and taking it through its normal range and noting any hyper or hypo-mobility in relation to adjacent vertebral levels. This is performed in supine lying and is routinely reassessed on subsequent consultations. If radiculopathy (referred pain in the limbs) or cervico-thoracic mechanical restriction exists, it will often be localised at this time of the assessment. Blood pressure in standing, lying and at end of range cervical rotation is also assessed though not always on the initial consult if range or pain is a limiting factor.

Physiotherapy treatment of the cervical whiplash patient

Once bony trauma and instability have been excluded, initial treatments (often lasting two to three weeks after the injury) focus on relieving muscular tightness. This may include basic massage techniques, deep tissue release, (pain permitting), trigger point needling, heat and gentle (but very frequent), stretching of the cervical, thoracic and shoulder musculature.

Once bony trauma and instability have been excluded, initial treatments (often lasting two to three weeks after the injury) focus on relieving muscular tightness. This may include basic massage techniques, deep tissue release, (pain permitting), trigger point needling, heat and gentle (but very frequent), stretching of the cervical, thoracic and shoulder musculature.

Patients are advised on a strict home procedure to follow after each treatment to minimise aggravation of their pain. It is important to inform the patient that short term (no more than 12 to 24 hours) tenderness may be present after such ‘muscular based’ treatments in the first 1 to 2 weeks. Beyond this time however, treatment seldom results in discomfort. Joint mobility treatments (mobilisations or occasionally manipulations) are slowly incorporated as well as strengthening the postural deep neck flexors, scapula retractors and cervico-thoracic extensors.

It is when the strengthening component of a patient’s rehabilitation is neglected that chronic or recurrent cervical problems are commonly seen. These can persist for many months or even years. As a general rule, the greater the delay in commencing such a routine, the longer it needs to be continued to gain positive results.

Initial intervention of the cervical whiplash patientKey points to observe in the management of whiplash patients

- Immediate, often prophylactic, pain management is essential – this needs to be reviewed regularly in the first few weeks to ensure its efficacy. Analgesics, NSAID’s, heat applications, relative rest and, if necessary, partial immobilisation.

- Education and support of the patient as to their involvement in their own rehabilitation as well as what to expect (both physically and emotionally) in the following months.

- Early introduction of soft-tissue based therapy (first few weeks). Other manual interventions may be appropriate if pre-existing or other regional injury exists.

- Inclusion of joint mobility techniques and exercises.

- Appropriate strengthening of postural muscles and functional retraining if required Whiplash patients are often scared, angry and in a great deal of pain. Perhaps beyond any other patient ‘type’ they require education and reassurance throughout the entire rehabilitation process.

If you have any further questions on this subject, or you would like to contact the physiotherapist best suited to managing your problem please call or email us.

© Andrew Thompson