Cervicogenic Headache

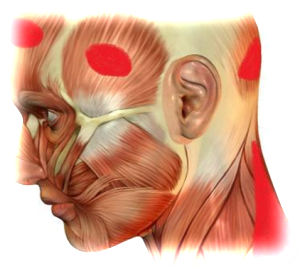

Cervicogenic (neck) headache is a secondary presentation of headache referred from articular (joint), muscular, neural and vascular structures in the upper cervical spine. Referral to the frontal, temporal and retro-orbital regions is thought to be due to the convergence of sensory fibres from the upper cervical spine and the trigeminal nucleus claudalis (descending tract of the trigeminal nerve).

Cervicogenic headache is one of the more common forms of headache constituting up to 20% of headache cases and has been found to be more prevalent in women than men.

Cervicogenic headache is one of the more common forms of headache constituting up to 20% of headache cases and has been found to be more prevalent in women than men.

A person with cervicogenic headache will typically feel that their headache is unilateral (one-sided) with pain in the suboccipital, frontal, orbital and temporal regions. The patient’s headache will be aggravated by movements of the cervical spine or sustained/repeated postures. Commonly associated signs are feelings of light-headedness, nausea, dizziness and in severe cases visual disturbances and tinnitus.

How is Cervicogenic headache diagnosed?

Diagnosis of cervicogenic headache will involve a thorough examination of the articular, muscular and neurovascular structures in the cervical spine in addition to a comprehensive assessment of spinal posture.

On assessment of the cervical spine a person will often present with reduced movement through the mid and upper cervical spine. This may be associated with tenderness and hypomobility through the C1-3 articulations.

Palpation over suboccipital tendons as well as the greater occipital nerve may increase pain or reproduce the headache. There may be an increase in palpable muscle tone through the suboccipital region, cervical erector spinae, upper trapezius and levator scapulae. It is also common for the sternocleidomastoid and scalenes to have active trigger points.

Muscle testing will often reveal weakness or poor muscle control of the deep neck flexors causing overly active muscles in the anterior neck. This is commonly associated with forward head postures and protracted shoulder girdles. In the case of neural symptoms being present a full neurological exam is performed to clear any further pathologies.

Physiotherapy Management:

Physiotherapy management will focus on restoring range of movement through the upper cervical spine and decreasing the patient’s pain. This will often involve using mobilisation or manipulation techniques particularly through the C1, C2 and C3 spinal segments. These can be performed in both lying and sitting.

Manual traction may also be utilised to facilitate stretching particularly of the suboccipital muscles and to assist with pain relief. Release of the soft tissues in the suboccipital region as well as the other major cervical musculature is essential to relieving the patient’s pain and would be supplemented by a targeted stretching home exercise program.

Correction of aggravating postures and retraining of poor movement patterns is crucial in preventing this becoming a chronic condition. This will involve exercises to increase the strength and control of the deep neck flexors as well as improving postural awareness and strength through the posterior shoulder girdle. In the case of someone who works a desk based job it would then be important to educate the patient on correct computer ergonomics to further reduce the risk of reoccurrence.

|

Note – the use of ultrasound, interferential, TENS or laser should never be considered in the management of headaches or migraines. These treatments have no benefit to treat ANY musculoskeletal pathology. Practitioners who endorse or use these should always be avoided. |

Medical management:

Oral analgesics and non-steroidal antinflammatory medication is the first-line treatment for cervico-genic headaches. Paracetamol, and non-steroidal antinflammatories (NSAIDs).such as Ibuprofen or Dicofenac. These are well suited to use whilst undertaking physiotherapy treatment.

Medications that accentuate muscle ‘relaxation’ can also be beneficial whilst manual treatment is undertaken – Oxazepam, Dantrolene. They should not be used in the acute phase of any spinal injury. These medications can induce drowsiness and should be prescribed with caution and for short-term use only whist manual therapy is undertaken. Neuropathic analgesics (Pregabalin, Gabapentin, Carbamazapine, Valproate) and even certain antidepressants (Fluoxetine, Desvenlafaxine , Cipramil) may also be prescribed.

In cases that are chronic or non-responsive to manual therapy, local anaesthetic ‘trigger point injections’ may provide significant relief. Performed alone however such injections rarely provide long-term relief and it is essential that such injections are given in coordination with physiotherapy treatment. There remains debate over exactly what a ‘trigger point’ is and whether such points have any physiological basis. The answer is….probably not. However local anaesthetic, when injected into muscle ‘knots’, can result is considerable relief of muscle tightness – more so when combined with manual muscle release techniques.

The mechanism by which such injections work is not fully understood and they should not be used as a treatment in isolation. It is thought that the anaesthetic effect of the injection reduces neural input to the muscle(s) (albeit short lived) and when this is combined with stretching and manual release of the muscles, long-term elongation and loosening can occur. Local anaesthetics also act as potent vasodilators. In so doing such injections serve to accentuate blood supply to knots and relive the pain of focal muscle ischaemia.

Corticosteroid may be added to the local anaesthetic and injected into tight muscle bands or their tendonous attachment. This serves to further relieve pain associated with fascial inflammation and tendonoses.

In cases where patients have had good but short-lived relief with tendon steroid injections, autologous blood injections or platelet rich plasma can prove a to be very effective long term or permanent treatment option.

Botulinum toxin (Botox®) injections can be beneficial in cases that have been responsive to local anaesthetic injections or when the headache is experienced in the temples and forehead.

Other Types of Headache:

There are many forms of headache for which physiotherapy is not indicated. Your physiotherapist should diagnose and distinguish such pathologies and refer you for appropriate management.

Cluster Headaches:

Cluster headaches occurs as a series of typically unilateral headaches with pain most often felt over the temporal, orbital and supraorbital regions. The headaches are often said to be severe in nature and can be associated with symptoms such as nasal congestion, eyelid oedema, restlessness or agitation and sweating through the facial and frontal regions.

Migraines:

Migraine is a moderate to severe form of headache which is believed to have a neurovascular cause. They are twice as prevalent in females to males and can have significant impacts on quality of life if left untreated. The pain itself is often pulsating in nature, aggravated by physical activity and may or may not be associated with symptoms such as photophobia, phonophobia, visual disturbances and nausea or vomiting. Read more in our section on migraines.

Tension Headaches:

Tension headache is a common form of episodic headache that is often mild to moderate in severity. Patients will often complain of bilateral pain or a tight compressing sensation around the head. It is not often associated with nausea or aggravated by any form of physical activity.

Headaches may also arise from the temperomandibular joint, ocular pathologies (glaucoma, orbital cellulitis etc), infection, (neuralgia, shingles etc), intracranial lesions (hydrocephalus, cancer, space occupying lesions etc) and numerous other autoimmune, neurological, haematological, vascular and endocrinological disorders. It is vital that all headaches are assessed for causes other than the neck. The physiotherapists at Kingsley Physiotherapy can assess and treat (or refer) as appropriate.

If you have any further questions on this subject, or you would like to contact the physiotherapist best suited to managing your problem please call or email us.

© Ms Kahlia Ferguson and Dr Andrew Thompson