Sever’s Disease

What is Sever’s Disease (Calcaneal Apophysitis)

Many of the bones that make up the human skeleton are formed by gradual ossification (bone formation) of an ‘immature’ cartilage matrix. As bone growth continues and the skeletal system matures growth plates remain in many of the bones. This cartilage ‘plate’ (called an ‘epiphysis’ or an ‘epiphyseal plate’) allows for the ongoing lengthening and strengthening of our skeleton as we progress through puberty to adulthood.

“Apophysitis” is the term given to inflammation of these growth plates. This most commonly occurs as a result of repeated or excessive stresses placed through the bone. Rare cases of septic apophysitis are seen (either in isolation or as a secondary development of osteomyelitis or systemic infection) but will not be discussed in this article.

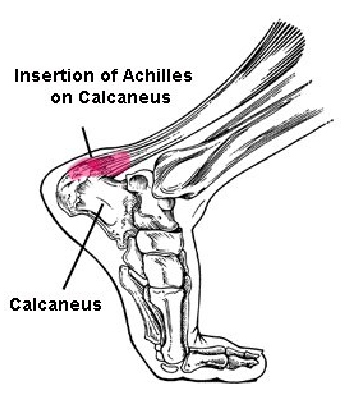

Sever’s disease (calcaneal apophysitis) is a common cause of heel pain in children between the age of 7 and 13 years old. Sever’s disease (SD) results in inflammation and pain around the growth plate of the calcaneum (heel bone). It is a condition that occurs during or after a time of rapid growth and is more commonly seen in the physically active child.

The repeated stresses placed through the calf muscle and the foot result in micro-trauma and small amounts of movement between the two, as yet, unfused bony portions of the calcaneum. This is called a ‘traction apophysitis’.

Signs/symptoms

The most common symptom of Sever’s disease is pain around the back or side margins of the heel during sporting activity – running and jumping in particular. Like plantar fasciitis, pain may be worse with

weight bearing after prolonged immobility – eg when standing after being seated for a period or upon waking in the morning. This however is not always present and in many cases of SD pain is only experienced during or after exercise.

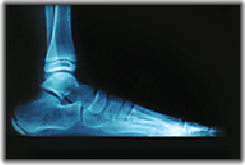

SD will cause tenderness over the back and particularly the sides of the heel bone. This tenderness is usually most notable on the inside (medial) margin of the heel. If you picture the location of the calcaneal apophysis in the above x-ray you can visualise the area that is most likely to be tender. Your physiotherapist may perform a “Squeeze test” by placing pressure on either side of the heel bone simultaneously – a positive test will illicit tenderness.

Swelling may also result in cases of SD although this is not common and other potential differential diagnoses (discussed below) should be fully excluded if swelling is significant.

How does Physiotherapy manage Sever’s Disease?

Your Physiotherapist will take a comprehensive history and perform a thorough assessment of the foot and ankle before diagnosing the condition. It is important that parents accompany their children to ALL consultations (irrespective of the pathology being treated) so that all necessary medical, genetic and even obstetric information can be discussed to formalise an accurate diagnosis. Many other pathologies can mimic the symptoms of SD and these need to be thoroughly examined as potential sources of pain in the adolescent foot. Some potential differential diagnoses include:

- Achilles tendonitis (tendinitis) – although uncommon in children this condition generally gives rise to pain in the bulk of the achilles tendon itself and seldom causes pain along the bone of the heel.

- Achilles enthesitis/enthesopathy – again this is rare in the adolescent patient and is discussed at length on this website.

- Retrocalcaneal bursitis – this can co-exist with SD and the treatment for this is not dissimilar.

- Jeuvenille arthritis (JA) – many forms of JA can lead to pain in the foot and ankle. Diagnosis of this problem requires a systemic (full-body) evaluation, a thorough history (from both the child and the parent) and in many cases requires blood testing. Your physiotherapist will direct you toward the appropriate testing and management of the various inflammatory, non-inflammatory and septic arthopathies that can affect children.

- Calcaneal fractures or stress fractures – again these are rare in the growing body and are more frequently associated with an isolated causative event.

- Septic arthritis, reactive arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and enteropathic arthritis – these pathologies require differentiation or exclusion by blood tests (including HLA-B27 and Rheumatoid factor) and by a detailed history and examination of the child. See “General Conditions” on this website for further information.

Your physiotherapist will then assess the child’s gait, footwear, and running style. Often calf muscle tightness in SD will result in limited range of movement at the ankle and your physiotherapist will provide stretches to correct this. X-rays or CT scans are seldom required in the diagnosis or management of SD. In older adolescent where the cessation of skeletal growth is uncertain or where the diagnosis is ambiguous an x-ray or ultrasound image may be useful.

Risk factors for Sever’s disease

There are several factors which can predispose a child to SD. These include:

- Gender – males are far more likely to have SD than females. Estimates range from 2:1 (male:female) to as high as 10:1.

- Growth and achilles tendon tightness – rapid growth is thought to be responsible for significant muscle-tendon imbalance in the growing body which places greater forces through the heel bone and hence the epiphyseal plate. Although there is no literature supporting this theory there has been widespread acceptance of the idea based on reduced range of movement in ankle dorsiflexion that accompanies many (though not all) sufferers of SD.

- High levels of activity and participation in sport – SD is almost exclusively seen in active children. Most notably sports or activities that involve considerable ballistic action (jumping, sprinting etc). Incidentally, comparative overuse, as seen at the beginning of a sporting season, may contribute to the development of SD.

- Biomechanical alignment and ‘environmental’ factors – faults with foot biomechanics (excessive pronation, pes planus) are very commonly seen in SD sufferers. Orthotic support, footwear advice and even lacing techniques will be discussed by your physiotherapist to augment the treatment of SD.

- Obesity – both impact forces and achilles tendon strain is increased in obesity and these factors are both thought to play a role in the development of SD in obese children.

- Trauma – injury to the calcaneum or the calf muscles have been discussed as a potential cause of some rarer cases of SD. This trauma may be acute or chronic (overuse) but denotes a very small percentage of reported cases.

- Infection – sporadic recorded cases of Brucellosis dot the literature but are considered by most to be a differential diagnosis rather than an alternate cause of SD.

Physiotherapy treatment of Sever’s disease

Although patients may be required to cease sporting activity for a 2-4 week period this is by no means required in all cases. Most often patients will be advised to modify or temporarily reduce their sporting activity whilst the following management strategies are implemented:

- Correction of foot biomechanics – this can take the form of orthotic shoe inserts, correction of inadequately supporting footwear, and correct lacing techniques to help stabilise the foot in the shoe.

- Calf lengthening – calf massaging and stretching will be advised. Seldom are resting splints (as used in achilles tendonopathies and enthesitis) required for the treatment of SD.

- Taping – during the acute management period, patients (or their parents) are instructed on how to tape the foot and the heel so that adequate support of the heel can achieved during sporting activity.

- Joint mobilisation techniques – your physiotherapist may use a variety of manual joint mobility techniques to augment joint movement where limitation exists. Most commonly this is required in cases of rear foot supination (rare) or in fixed-foot (usually congenital) deformity.

- Cryotherapy or contrast applications – the application of ice after sporting activity often relieves the acute pain associated with SD. Contrast applications (the use of alternate hot and cold compresses) has been found to assist in the management of numerous other superficial inflammatory pathologies and is though to hasten return to full sporting activities in sufferers of SD. Contrast applications are generally encouraged in the management of subacute and chronic cases of SD.

- Anti-inflammatory and analgesic medications – care should be taken when prescribing medication of any sort to the child or adolescent patients. Seldom is medication beyond paracetamol and/or simple non-steroidal antinflammatories (such as Ibuprofen) recommended and this should be considered only for short-term use in the initial management phase.

Corticosteroid injections (local or intramuscular) and surgery are generally contraindicated in Sever’s disease and all treatment avenues should be exhausted before these are considered.

Sever’s disease is a self-limiting condition – all cases will eventually resolve once the bones of the foot have ceased growing. If untreated the pain of SD will usually settle by around 6 to 12 months or when skeletal maturity is reached (in males this is usually around age 15-16 and in females by age 14-15). Physiotherapy can generally manage SD and aim to have patients return to full sporting activity within 2-4 weeks. Although there is thought to be no long-term problems associated with SD, many of the biomechanical foot deformities that are commonly seen in SD sufferers can predispose adults to other foot, shin and knee problems later in life. Your physiotherapist will discuss the need for ongoing orthotic use (beyond the termination of symptoms) if this is deemed necessary.

Sever’s disease is a common problem that is both quick and cheap to treat. If you have any further questions on this subject, or you would like to contact the physiotherapist best suited to managing your problem please call or email us.

© Sarah Adams, Andrew Thompson