Vertigo

What is vertigo?

In its simplest presentation, vertigo is described as the sense of ‘spinning’ or ‘whirling’ when the body is actually stationary. More commonly, people use the term ‘vertigo’ to describe a feeling of dizziness. Technically this is not entirely accurate and many sufferers of vertigo will be able to differentiate the sensation from the dizziness one might experience after spinning on an office chair.

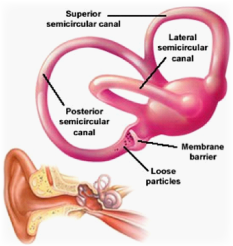

Vertigo is broadly classified into two main categories depending on the location (anatomically) of the dysfunction balance mechanism. “Peripheral” vertigo is caused by impaired functioning of any part of the vestibular apparatus – that part of the inner ear that is responsible for sensing our body’s position or sense of movement. “Central” vertigo results from damage (permanent or temporary) to the nerve (vestibular nerve) or brain regions that are responsible for transmitting or interpreting information from the vestibular apparatus.

What causes vertigo?

There are numerous causes of vertigo. Your physiotherapist will take a detailed history and perform a thorough examination to exclude some of the many causes of vertigo that physiotherapy CANNOT treat. Temporary periods of vertigo may be attributable to external factors such as dehydration, alcohol or drug intoxication or may follow head trauma, concussion or extreme emotional or physical stress. Systemic illnesses (even a cold of flu) can also cause transitory vertigo. More specifically damage to the inner ear balance mechanism (via illness, infection or injury) can also result in both short and long term periods of vertigo.

Although this webpage will focus on one of the most common causes of vertigo (Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo –BPPV), other potential sources include: hypotension, labyrinthitis, Meniere’s disease, vestibular neuritis (neuronitis), and damage to the visual or balance centres of the brain. Meniere’s disease will also be discussed in this web page as it is not uncommon for patients to present to physiotherapy with this condition. It is important to note however that with Meniere’s disease (and many other causes of vertigo), physiotherapy primarily plays a diagnostic, educational and referral role rather a therapeutic one.

Meniere’s disease

This is a progressive disorder affecting the balance and hearing functions of the ear. It is believed to result from impaired drainage of the fluid (endolymph) that fills the semicircular canals of the inner ear – it is the flow of endolymph through these canals (in relation to the skull) that allows us to judge the positioning of our body in relation to the environment around us.

Sufferers of Meniere’s disease may experience periods of vertigo (dizziness), tinnitus (ringing in the ears) and hearing loss which may progress over time. The latter of these two symptoms may occur in one or both ears and sufferers may also report a feeling of pressure of ‘fullness’ in the ears.

Although severe (often incapacitating) attacks generally last no longer than 24 hours. Hearing often returns after an attack but may progressively decline over time. It is also common for sufferers to feel acutely unwell during an attack – nausea and vomiting may accompany vertigo. The diagnosis of Meniere’s disease is essentially a process of exclusion (ruling out other afflictions that present in a similar fashion). As such, patients may be instructed to have hearing tests or imaging techniques (such as MRI) to exclude intracranial pathologies, inner ear or 8th-cranial nerve dysfunction.

Treatment is multi-faceted and includes: balance retraining, stress management and diet control (low salt intake, manganese supplementation and avoidance of artificial sweeteners have anecdotal benefit). Medically, anticholinergics, lipoflavinoids (vitamins C, B’s and bioflavinoids), steroids and diuretics aim to reduce pressure within the semicircular canals – none of these have shown consistent results across patients for the treatment of Meniere’s disease. Antiviral medication has also shown some promise in treating the symptoms of Meniere’s disease although its efficacy tends to diminish with time.

Finally, surgery may be suggested to patients suffering unbearable symptoms. This may take the form of a chemical labyrinthectomy (where a drug is injected into the middle ear to destroy the balance apparatus) or surgically cutting the vestibular nerve (the nerve responsible for transmitting balance signals to the brain). Ultimately the inner ear itself can be removed (labyrinthectomy). Such surgical treatments often remedy the vertigo component of the disorder and although this may not be of long term benefit, the unaffected ear can effectively take over the sensation of balance and body positioning very effectively.

Your physiotherapist will discuss these management options with you, provide you with a balance retraining programme and will refer you to a medical specialists best suited to managing this condition. Note, spinal manipulation plays no role in the management of vertigo and caution should be observed with practitioners who preach otherwise.

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo

BPPV, also called simply ‘benign positional vertigo’, is characterised by episodes of vertigo induced by specific movements (positions) of the head. Within the balance apparatusof the inner ear small collections of calcium crystals (otoliths), necessary to stimulate sensory nerve endings that translate our vertical and horizontal position in space, become dislodged and migrate towards the semicircular canals – the fluid filled canals (opposite) that allow us to judge rotatory movements of the head in three planes of movement.

Patients will describe transitory periods of vertigo (usually lasting less than one minute) that are brought on by movement of the head – often moving from lying to sitting, turning the head or when returning to an upright position having been leaning forward. It is common for nausea and vomiting to ensue.

Once again, your physiotherapist will not only assess the condition in order to exclude other more sinister causes of vertigo but also to localise the problem to either the left or right ear. A simple manoeuvre (called the “Dix-Hallpike test” or the “Hallpike manoeuvre”) will generally suffice to determine which ear is involved. Here the patient is taken from a sitting position with their head turned 45 degrees to one side and then gently lowered to supine (so that they are now lying on their back) with their head remaining turned to one side. In the clinical setting this is done with the patients head held over the end of the bed (though if this is done on the floor a pillow can be placed between the shoulder blades) so that the head is allowed to be held in an extended position at the same time (pictured left). If the patient reports a sense of vertigo or if nystagmus is observed (rapid darting movements of the eyes) the test is deemed to be positive to the ear on the side to which the patient’s head is turned. The patient is also observed after they return to the original sitting position.

Once again, your physiotherapist will not only assess the condition in order to exclude other more sinister causes of vertigo but also to localise the problem to either the left or right ear. A simple manoeuvre (called the “Dix-Hallpike test” or the “Hallpike manoeuvre”) will generally suffice to determine which ear is involved. Here the patient is taken from a sitting position with their head turned 45 degrees to one side and then gently lowered to supine (so that they are now lying on their back) with their head remaining turned to one side. In the clinical setting this is done with the patients head held over the end of the bed (though if this is done on the floor a pillow can be placed between the shoulder blades) so that the head is allowed to be held in an extended position at the same time (pictured left). If the patient reports a sense of vertigo or if nystagmus is observed (rapid darting movements of the eyes) the test is deemed to be positive to the ear on the side to which the patient’s head is turned. The patient is also observed after they return to the original sitting position.

After an episode of BPPV, some people continue to experience a degree of vertigo and may experience symptoms with fast movements or turning. Physiotherapy can provide further assessment of your balance and vestibular system and provide advice and exercises to promote return to normal.

Physiotherapy treatment of positional vertigo

Once it has been established which ear is involved a second technique called the “Epley manoeuvre” is applied. The following is the instruction for vertigo caused by right sided disease:

- The patient is seated on the bed with the head slightly extended (held backwards and turned 45 degrees to the right.

- With the head maintained in this position the patient is then told to lie back (either with a pillow between the shoulder blades or with the head supported over the end of the bed so that the head can be maintained in an extended position). The patient maintains this position for one minute or until all sensation of vertigo has ceased.

- The patient’s head is turned to the left whilst maintaining the extended neck position and again this new position is held for a further one minute or until all dizziness has subsided.

- The patient is instructed to maintain their head position in relation to their left shoulder whilst the patient then rolls onto their left side (the patient should now be staring towards the ground). This position is maintained for a further one minute or until all dizziness has resolved.

- Finally the patient is bought back to a sitting position and monitored for a further one minute.

One or more of the positions described above can evoke a sense of vertigo in the patient and may even induce vomiting. It is important that each position is maintained until full resolution of dizziness is achieved. Coaxing a patient through this uncomfortable time is often half the battle. This procedure usually brings about relief of symptoms within 24 hours (often much sooner) although it may have to be repeated a second time in order to fully treat the condition. This routine is taught to the patient (as reoccurrence of BPPV is not uncommon) and can readily be performed at home using the guidelines above. If the left ear is suspected to be the cause of BPPV, simply reverse ALL directions outlined in points 1 to 5 above (ie replace ’left’ with ‘right’ and right’ with left’). In cases that do not respond well to this manoeuvre and where BPPV remains the suspected diagnosis other, more intense regimes will be introduced by the physiotherapist and these often need to be carried out over several weeks with strict adherence to a home exercise regime. In such patients, medications such as prochlorperazine may provide adequate short term relief and in some cases can subdue symptoms indefinitely.

If you have any further questions on this subject, or you would like to contact the physiotherapist best suited to managing your problem please call or email us.

© Andrew Thompson