Acute, Chronic and Recurrent Ankle Sprains

What is an ankle sprain?

The terms ‘sprain’ and ‘strain’ are often used interchangeably. Technically, they refer to the injury of different tissue types. ‘Sprains’ involve the damage or tearing of ligaments (the fibrous tissue that connects bones) whist ‘strains’ imply damage to muscle or tendon. A sprained ankle is a very common injury and is not confined to the sporting arena.

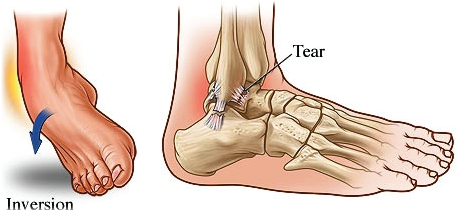

Most commonly (though not always) a sprained ankle involves some degree of rapid (and uncontrolled) inversion of the ankle joint – inward twisting or ‘rolling’ of the ankle (see opposite).

The injuries sustained in this process can be extensive and extremely varied. Mild injuries can result in stretching (with or without tearing) of the ligaments that support the ankle whilst more severe injuries may result in bone fractures or damage to the surrounding nerves.

The physiotherapy assessment of a sprained ankle

As with all presentations, your physiotherapist will take a detailed history from you first. This will include a description of the mechanism of the injury (was this injury sustained whilst running forward, backward or landing after jumping etc) as well as an outline of associated and subsequent symptoms – did swelling evolve rapidly, was there an audible ‘crack’ or ‘snap’, is there any numbness or pins and needles in the foot etc. You will also be asked about previous foot and ankle injuries that you have sustained and the diagnosis that was given to you at the time of these events. You will be asked about the nature of your sport (the level of competition, playing surface etc) as well as your footwear, general fitness and expectations for returning to sport.

Your physiotherapist will then focus on a clinical assessment of your ankle injury. This will include assessing bony structures for potential fractures or dislocations, assessing neural and vascular structures (nerves and blood vessels) for evidence of neurovascular compromise and finally the assessment of all other soft tissues around the ankle – ligaments, tendons and muscles.

An accurate diagnosis is essential in order to formulate an appropriate treatment plan. If rehabilitation is either misdirected or rushed because of a poor initial diagnosis, the long term complications and potential for recurrent injury is enormous. At Kingsley Physiotherapy we offer our “Diagnostic Consultations” for people wishing to receive an accurate diagnosis and home-treatment plan without the cost of ongoing physiotherapy. (See “How we differ” for more information).

Ankle x-rays are one of the most over-prescribed investigations and frequently yield very little useful information that will guide a patient’s rehabilitation. Talk to your physiotherapist about why an x-ray may or may not be necessary. Unless a thorough physical examination is carried out and clinical suspicion of an underlying fracture is genuinely considered, x-rays can be a needless expense.

The physiotherapy treatment of a sprained ankle

The role of physiotherapy in the treatment of a sprained ankle has come a long way from the passive interventions of a decade ago. Machine based therapies such as ultrasound and laser have consistently been shown to provide no substantial benefit to the healing or recovery time of such injuries. In most cases, manual therapy can be commenced within 24-hours of the initial injury. Once a diagnosis has been made and the possibility of bony or neurovascular injuries has been excluded, your physiotherapist will commence progressive mobilising (loosening) of the soft tissues around the ankle. This should not be painful and care needs to be taken to minimise the stresses placed through damaged or inflamed structures – secondary tissue damage (either through overly aggressive treatment or from the subsequent ischaemic insult that arises from the compounding of swelling around the injury site) is not uncommon if treatment is carried out by an inexperienced or overzealous practitioner.

The aim in the early days of treatment is not only to minimise swelling around the injury (excessive swelling can obstruct adequate blood flow to the damaged tissues, delay healing and cause secondary tissue damage) but also to restore normal and pain free movement to the ankle. Range of movement should be restored so that a normal gait pattern (sufficient dorsiflexion during mid-stance and pre-swing) can be achieved as soon as possible. Enabling a patient to achieve a normal and symmetrical gait pattern early in the rehabilitation is shown to significantly enhance tissue repair and tensile tissue strength.

Your physiotherapist will also tape the ankle following each treatment session. This is a skill that can readily be taught to a willing friend so it is advisable to bring someone to accompany you during your first consultation. The aim of taping is 2-fold – firstly to apply pressure to the site of injury (this assists with the alleviation of pain and the removal of excessive swelling from around the damaged tissues) and secondly to provide stability and support to an otherwise unstable ankle. Taping gives a patient considerable confidence in their ankle (knowing that they are very unlikely to re-injure the ankle when it is properly taped) and in so doing encourages a normal gait pattern much sooner in the rehabilitation process.

Note: The ligamentous structures on the outer side of the ankle that are commonly damaged during inversion injuries are superficial enough to benefit from regular applications of ice in the first 24-48 hours (see the “SELF HELP” tab at the top of our home page for more information about the application of ice following an injury). Your therapist may even pack the ankle in ice after the first few treatment sessions to minimise any swelling that ensues. However, applying ice (with or without the addition of electrical stimulation) should NOT constitute a treatment in itself.

Once the initial pain and swelling has settled, you will be encouraged to graduate your return to activity. Putting ‘normal’ stresses through these repairing tissues produces a better functional outcome in the long-term and (arguably) improves the tensile strength of newly formed fibrotic (scar) tissue. Your physiotherapist will instruct you on how to progress your training regime so that the ankle can cope with the increasing physical demands it encounters as you resume your regular sporting activities. This rehabilitation process can vary significantly depending on the sport and the level of competition. Often you will continue to have the ankle taped or braced during these early attempts at sport. Neither taping nor bracing will cause weakening of the ankle musculature. There are no proven long-term adverse effects of bracing or taping the ankle either. This is not always the case for other regions of the body that may require taping or bracing.

The management of recurrent ankle sprains

Once an ankle has suffered an inversion sprain there are several factors which make recurring injuries more likely:

- The intrinsic stability (or instability) of the ankle joint – how stable (or loose) are the joints of the foot and ankle now that some of the support structures have been damaged?

- A lack of control and feedback from the ankle joint – proprioception (discussed below)

- An increased demand placed on the joint – as the athlete progresses with their sporting activities, higher level competition and increased training demands place additional workloads on the foot and ankle.

- Biomechanics of the foot – is there an increased demand placed on the joint because of poor fitting footwear, flat feet or ‘poor’ running style?

To reduce the risk of reoccurrence, all of these factors need to be addressed by your physiotherapist.

How will physiotherapy help to prevent recurring injuries?

1. The stability of the foot and ankle can only be altered by providing additional external support – braces, taping etc. Other joints in the body – the shoulder, hip, spine etc – can be supported by an appropriate strengthening regime. These are all joints that receive a significant proportion of their stability from muscular structures (as opposed to ligamentous structures or bony anatomy).

The ankle on the other hand receives the overwhelming majority of its stability from the bony structure of the talocrural joint and from the ligaments that surround the joint. The joints that make up our fingers are similar – they can only bend and straighten to a certain point and no amount of strengthening will alter this. If the ankle remains loose (unstable) following an injury, your physiotherapist may discuss appropriate ankle braces or taping techniques that can provide additional support and considerable injury prophylaxis. Because the ankle has very little musculotendonous support, ankle braces DO NOT lead to weakness of the joint even if worn extensively.

2. ‘Proprioception’ can be thought of as the ability to sense the position or movement of a joint. Try closing your eyes and holding the fingers of your left hand in random positions. Then, without looking, see if you can mimic this pattern with your right hand. Your two hands should match almost exactly. The reason you are able to do this is because of the ability you have to sense the position of each of the small joints in your fingers. This feedback is provided to your brain by microscopic stretch receptors in the muscles, tendons and ligaments that surround your fingers (muscle spindle fibres and golgi tendon organs).

These stretch receptors also detect when a joint is being overstretched and may be vulnerable to damage – try bending your fingers back as far as they can go. When ligaments or tendons are damaged they lose their ability to perceive stretch as effectively – the resulting scar tissue is not equipped with these stretch receptors. Consequently, damaged joints can be more susceptible to reinjury as they are less able to sense (and correct) the joint position when a joint is forced beyond its normal range of movement.

Proprioception exercises may be prescribed by your physiotherapist as a means of retraining those tissues that remain intact and functional around the injured joint. The reality is however that for a proprioception programme to be effective it has to be performed regularly (several times per day) for many months. It is debatable if such programmes truly have any long term effect on reducing the likelihood of reinjuring the joint. It is a difficult thing to accurately research. Studies that have confirmed it as an effective rehabilitation regime have been carried out on elite level athletes (who have the time and dedication to commit to the programme) and are based on relatively small retrospective cohorts. Several prospective control studies (research aimed at comparing a given intervention with a control/non-intervention group have provided less convincing evidence for proprioceptive rehabilitation). Despite this, it remains a good theoretical approach to minimising the risk or reoccurrence in many types of joint injury (along with other interventions discussed in this website) and is regularly included as part of ankle, knee and shoulder rehabilitation.

3. Your physiotherapist will also help graduate your return-to-sport programme. Ideally, this should be done by a therapist who is familiar with the particular demands your specific sport places on the joints of your body and how such stresses may affect the repair of injured tissues. This is even more crucial when injuries arise in the growing body. Injuries that occur in childhood or adolescence can hamper the development of growing bones (if fractures occur through growth plates) or lead to premature arthritic change in adult life when joint stability is compromised. Furthermore, injuries that occur at this time can not only impede the enthusiasm of young athletes but commonly cause children and teenagers to cease engagement in aerobic sporting pursuits.

The ideal rehabilitation regime should not only ensure maximum recovery following an injury but should serve to reignite the desire to continue progressing with sporting activities. The physical and social benefits of sporting involvement invariably outweigh the pain or cost of the periodic injuries that may ensue.

4. Biomechanics is perhaps the most important factor of injury prevention following a sprained ankle. Biomechanical factors that can contribute to re-injury include:

– Poor fitting footwear – your physiotherapists will assess the shoes you wear when playing sport to determine their suitability for your foot ‘type’ (discussed below), the sport you play and the surface(s) you play on. A simple adjustment to the type of shoe you wear or even the lacing process can make a world of difference to the support your foot receives.

– Alternate gait patterns and running styles – this needs to be assessed by an experienced physiotherapists who is familiar with your sport and the specific demands it places on the foot. Many people who have seemingly “normal” walking styles, have significant loading and unloading defects when they run. The only way to assess this is by meticulous analysis of a person’s walking and running styles on a treadmill (or on the field). Re-education of one’s running style can be a tedious process but can make an enormous difference in an athlete’s performance on-field. Similarly, correcting aberrant biomechanics can play a significant role in the prevention of injury in the sporting arena.

– Intrinsic biomechanics – Assessing “foot type” is a fascinating area of physiotherapy in its own right – to be able to accurately assess the movement of the many components of the foot during a normal gait/running cycle is a challenging skill to master. Common biomechanical defects that may lead to recurrent ankle sprains include:

- Excessive plantar flexion of the first metacarpal

- Excessive mid foot pronation

- Rear foot pronation persisting from early/mid-stance to terminal stance

- Excessive mid and forefoot laxity

- Marked rear foot supination (rare).

Many of these biomechanical dysfunctions can be treated with manual therapy and appropriate orthotic support.

Numerous other anomalies play a role in recurrent ankle sprains. Variances in gait pattern according to gender also need to be considered – women, for example, have exaggerated lateral pelvic sway during mid stance and pre-swing and have a reduced stride length (compared to male leg length and body height). This may be a contributing factor to the increased occurrence of ankle sprains in female athletes but unfortunately is not something that can readily be corrected. Likewise, it appears that the timing of a woman’s menstrual cycle can also vary their susceptibility to ligamentous injury (anterior cruciate ligament injuries have been most extensively researched) but little can be done to alter this.

Summary

Ankle injuries are one of the most common reasons for presentation to a physiotherapist. They are often under-judged and mistreated with a banal sense of familiarity. Ankle injuries require an observant eye, a pragmatic and formulated approach, but above all, they need to be assessed with the due caution and scepticism of a keen-eyed detective.

If you have any further questions on this subject, or you would like to contact the physiotherapist best suited to managing your problem please call or email us.

© Andrew Thompson