Sciatica and Piriformis syndrome

What is sciatica?

Sciatica is a broad term encompassing several  pathologies that give rise to irritation or

pathologies that give rise to irritation or

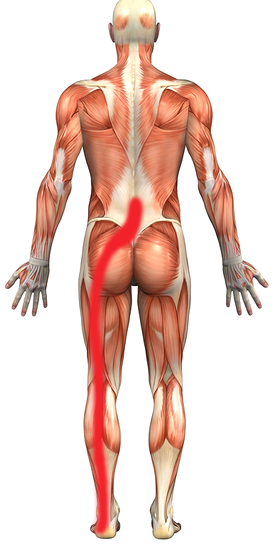

entrapment of the sciatic nerve. Symptoms are highly variable but may include pain, numbness or paraesthesia in the region of the lower limb innervated by the sciatic nerve (opposite). The symptoms of sciatica most commonly affect only one side of the body. Most causes of sciatica arise from the lumbar spine – specifically the nerve roots of the lumbosacral plexus that join to form the sciatic nerve.

Piriformis syndrome is considered a type of sciatica and occurs when the sciatic nerve is irritated by the piriformis muscle. It has been a controversial diagnosis that is often made on clinical grounds and by excluding other causes of lumbar pain and sciatica. Magnetic resonance neurography and EMG studies (performed whilst the piriformis muscle is stretched) can confirm the diagnosis or exclude other causes of symptoms.

The symptoms of sciatica may be aggravated with tasks that involve repetitive or prolonged flexion of the lumbar spine (including sitting) and may be relieved by short periods of standing or lying.

The pain of piriformis syndrome may be aggravated by sitting and sustained lumbar flexion but may be relieved by standing or walking with the effected leg held into external rotation.

How is sciatica diagnosed?

The diagnosis of sciatica is often made on clinical presentation alone. A thorough examination of the lumbar spine, sacroiliac joint, hip joint and lower limb muscles is essential. Clinical examination should include assessment of lumbar movement (which can help differentiate compression of the nerve roots caused by disc herniation or stenosis), lower limb neurology (reflexes, power, tone and sensation) and specific orthopaedic testing. ‘Straight leg raise’ and ‘slump’ testing are non-specific clinical assessments for sciatic nerve involvement.

Imaging (CT or MR) may be requested to confirm the diagnosis or in refractory presentations when semi-invasive or surgical interventions are being considered. As with most lumbar pathologies, plain film x-rays add very little to the diagnosis, prognosis or management of sciatica.

Aetiology of sciatica

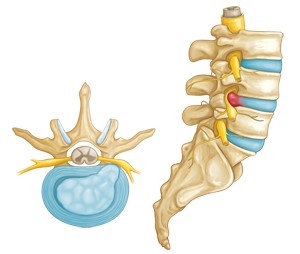

One common cause of sciatica is lumbar disc herniation that results in compression of the S1 nerve root. Intervertebral discs act like cushions that separate individual vertebrae in the spine. They are comprised of an inner gel-like nucleus surrounded by layers of fibrous cartilage-like tissue. Injury to these fibrous layers may lead to extrusion of the nucleus and compression of the nerve root (opposite).

Symptoms of sciatica may also arise when the patency of the intervertebral foramen (the ‘hole’ through which the nerve roots exit the spinal canal) is compromised. This is called spinal stenosis and may result from narrowing of the intervertebral disc (spondylosis or degenerative disc disease), the development of osteophytes that encroach upon and narrow the foramen, or instability of the vertebral column leading to spondylolisthesis.

Piriformis syndrome has a less clear-cut aetiology. Hypertrophy or spasm of the piriformis muscle can lead to sciatic nerve entrapment and can be caused by lumbar or sacroiliac joint pathology or by postural/ergonomically induced muscle imbalance around the pelvis. The mechanism of this type of entrapment neuropathy is complex and treatment requires a practitioner with a solid understanding of lumbo-pelvic biomechanics. Aberrant variations in the anatomical pathway of the sciatic nerve as it passes the piriformis muscle may account for a minority of cases.

Treatment of sciatica

Focused manual treatment is dependant on ascertaining the exact cause of sciatic nerve entrapment. In cases of discogenic sciatica analgesic and anti-inflammatory medications are vital. In such cases manual therapy may involve releasing tight muscles around the lower lumbar spine and gluteals. Physiotherapy treatment will progress to loosen (mobilise) the lower lumbar vertebral levels and relieve compression on the intervertebral disc. Traction may be utilised to reduce pain that is referred into the lower limb though this technique needs to be applied with caution as it can worsen pain in the lumbar spine. Taping or bracing the lumbar spine between treatment sessions may be necessary to minimise flexion posturing.

Exercises will be prescribed to facilitate segmental rotation and extension of the lumbar spine. The timing and progression of these exercises is crucial.

Note – Thrust manipulation of the spine should be avoided in all presentations of spinal nerve entrapment.

Beyond oral, parenteral or rectal analgesia, medical treatments may include corticosteroid root sleeve, facet joint or epidural injections. The choice of injection is best guided by the correlation of lumbar movement restrictions with appropriate imaging – CT, MR or nuclear imaging (bone scan) are the preferred imaging options. It is worthy to note that sacroiliac joint dysfunction (a potential cause of sciatica) is not well detected using any of these imaging modalities.

Surgical interventions may be required in refractory cases of sciatica. These include: discectomy, laminectomy, fusion or disc replacement. Click here for a more detailed outline of surgical treatment options. Sciatic pain that is not relieved by non-weight bearing postures (lying) or where nerve compression leads to a loss of deep tendon reflexes or flaccidity and weakness of the muscles supplied by the sciatic nerve, more frequently require surgical intervention.

Piriformis syndrome often requires a complex treatment regime and involves both stretching of the piriformis and gluteal muscles and strengthening of the hip abductors, extensors and external rotators. Recovery can be significantly augmented with corticosteroid injections to the piriformis muscle and its tendon and to the medial gluteal tendons. Your physiotherapist may suggest you see one of the doctors at Kingsley Medical to perform these injections.

The vast majority of people experiencing sciatica will not require surgery to resolve their symptoms. Most will be pain free within 8 to 12 weeks. When administered appropriately and coordinated with medical interventions, physiotherapy treatment can reduce this recovery period to around 2 to 3 weeks.

If you have any further questions on this subject, or you would like to contact the physiotherapist best suited to managing your problem please call or email us.

© Blake McConville and Andrew Thompson