Patello-Femoral Syndrome

What is patella-femoral syndrome?

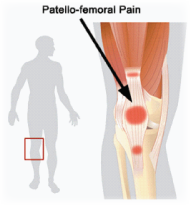

Patella-femoral syndrome (PFS) is the most common presentation of knee pain to Kingsley Physiotherapy in patients under the age of 50. Sadly it is a condition that is frequently mismanaged, even when accurately diagnosed. PFS is caused when the patella (kneecap) tracks in a poor position when the knee is bending and straightening. There are several reasons that this can occur including anatomical variances in the structure of the knee/patella, poor or altered foot biomechamics and muscle imbalances around the thigh or pelvis. It is a very common cause of knee pain in the active teenager but can nearly always be remedied quickly and cheaply without the need for surgery.

Patella-femoral syndrome (PFS) is the most common presentation of knee pain to Kingsley Physiotherapy in patients under the age of 50. Sadly it is a condition that is frequently mismanaged, even when accurately diagnosed. PFS is caused when the patella (kneecap) tracks in a poor position when the knee is bending and straightening. There are several reasons that this can occur including anatomical variances in the structure of the knee/patella, poor or altered foot biomechamics and muscle imbalances around the thigh or pelvis. It is a very common cause of knee pain in the active teenager but can nearly always be remedied quickly and cheaply without the need for surgery.

Physiotherapy assessment of patella-femoral syndrome

Patients will commonly present with pain around the patella that has developed over a period of time without any traumatic causative event. It will often develop in the patient’s mid and late teenage years but is also seen when comparatively sedentary adults commence exercise or gain weight. For this reason, pregnant women are also susceptible to PFS – often it is their knee pain that prevents them from returning to exercise post-partum.

Patients may complain of pain with running but particularly with squatting/lunging, climbing or descending stairs/inclines as well as kneeling. There may be tenderness around the superior margin of the infra-patella fat pad (the soft boggy tissue immediately below the patella) and along the inner and lower border of the patella – this is assessed by deviating the patella inwards whilst the knee is fully straightened and pressing along the under surface of the protruding patella.

It is important to remember that PFS commonly co-exists with other conditions such as infra-patella fat pad impingement, pre-patella bursitis, supra patella bursitis (*) and even osteo and rheumatoid arthritis – not only do we see patients with arthritic degeneration of the patella-femoral joint but commonly in the lateral tibio-femoral compartment as well. For this reason, if medial knee joint pain presents, medial meniscal or medial tibio-femoral compartment degeneration must be excluded, even in the absence of traumatic insult. Careful anatomical palpation will also rule out patella tendonopathy, Osgood-Schlatters disease and pes-ansurine bursitis. It is unfortunate, but many patients with patella-femoral symptoms are told that their knee pain is the result of age-related degeneration and that they must tolerate their pain or manage it with anti-inflammatory drugs until their pain is severe enough to warrant a knee replacement. This is seldom the case.

(* a well positioned cortisone injection will usually resolve most of these conditions and physiotherapy is only required in cases of reoccurrence)

The teenage female is particularly at risk of developing PFS, not only because of netball (a sport which, for its numerous hazards, also accentuates the outer thigh and gluteal musculature) but because of the broadening female pelvis that develops during puberty. This then augments the effect of the iliotibial band and gluteus maximus on the lateral tendonous attachment of the patella. The resulting muscular imbalance is also commonly seen in cyclists of both sexes.

The teenage female is particularly at risk of developing PFS, not only because of netball (a sport which, for its numerous hazards, also accentuates the outer thigh and gluteal musculature) but because of the broadening female pelvis that develops during puberty. This then augments the effect of the iliotibial band and gluteus maximus on the lateral tendonous attachment of the patella. The resulting muscular imbalance is also commonly seen in cyclists of both sexes.

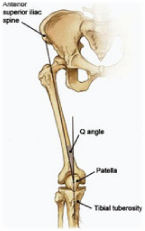

Once a patient’s history is fully understood, physical assessment can begin. Patients are first observed in standing. A patient’s Q-angle is measured (the acute angle formed by lines drawn from the midpoint of the patella to the anterior superior iliac spine and from the tibial tuberosity through the midpoint of the patella – opposite). The patient’s foot position (internal or external rotation) and their foot biomechanics are also assessed – PFS is often accompanied by forefoot pronation (with or without pes cavus) or, less frequently, rear foot pronation. It is important to note that PFS can exist in patients who supinate in stance or during gait but this is more commonly associated with muscle imbalances around the hip and pelvis – excessively strong/tight gluteus maximus or iliopsoas as seen in skaters, cyclists and dancers or marked weakness of gluteus medius, more commonly seen in males especially those with a posterior pelvic tilt or loss of lumbar lordosis.

The patient is then observed during walking and running. Marked changes in lower limb positioning, lateral pelvic sway, tibial rotation and foot placement can be observed during a gait assessment. Patients will then be asked to lunge, squat and perform resisted knee extension from 90o flexion. This will often evoke their pain. If cracking or grinding exists with these movements, one may also suspect chondromalacia of the patella. Likewise, any audible occurrence should prompt a full assessment of the menisci and chondral cartilages.

Swelling, if present, will generally manifest around the infra patella or lateral-suprapatellar region. One can easily assess fluid accumulation in the supra patella pouch by firmly pressing the region above the patella as it ‘falls-off’ into the quadriceps tendon. This may produce a palpable bulge or ridge and, if extreme, may require aspiration to hasten recovery.

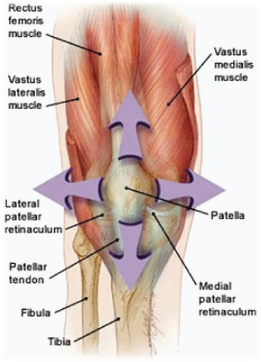

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the exact nature of the patella mal-positioning must be assessed. There are potentially four planes of abnormal movement/positioning ofthe patella that may be responsible for the patient’s symptoms. It is often thought that PFS is simply a problem caused by the lateral tracking of the patella during contraction of the quadriceps. One must also assess lateral tilting, patella alta/baja and, in rarer cases, patella rotation – in instances where rotational abnormality is suspected, lateral rotation of the patella apex is usually the cause.

X-rays are extremely helpful in cases of PFS. Lateral views in 90o knee flexion help ascertain baja and alta abnormalities whilst superior views of the patella (taken in knee flexion) demonstrate the lateral tilt and drift. The positioning of the patella (including patella rotation) is best viewed with a patella CT scan although generally a plain film x-ray will suffice and CT’s are considered only in cases that do not respond to physiotherapy intervention or where surgery is imminent. Remember, it is not uncommon for two or more abnormalities of position to co-exist in the one patient. If the exact cause is ambiguous, one can easily tape the patella to temporarily correct each of the four positions individually (in isolation) and reassess the patients presenting symptom – eg ask them to squat, lunge or run with a particular taping in situ.

Physiotherapy treatment of patello-femoral syndrome

Treatment of patella alta or baja (the patella sits too high or too low) is nearly always the task of the surgeon (unless of course this is not the cause of a patients symptoms but exists arbitrarily). Lateral tilting and tracking of the patella are managed in three steps – the application of these is variable depending on the specific presentation.

- Correction of any lateral-thigh muscular or tendon tightness – treatment may include stretching of the lateral patella retinaculum (often described as “medial patella glides”), releasing of the gluteus maximus and ilio-tibial band (ITB), as well as hamstring releasing (biceps femoris exclusively) and superior tibio-fibular joint mobilisations. The patient is also given stretches to perform at home for the ITB, gluteus maximus, iliopsoas and lateral quadriceps if necessary.

- Strengthening of muscular weakness – generally this involves specific exercises to bias Vastus Medialis Obliques (VMO). This is often described as a “McConnell regime” after the Australian physiotherapist Jennifer McConnell who pioneered much of the treatment and research into this condition. VMO exercises are not only designed to facilitate contraction of the oblique fibres of vastus medialis in relation to the other quadriceps muscles but also to assist contraction on the muscle in a functional sense – particularly in the last 20o of knee extension. Where pelvic muscular imbalance exists, gluteus medius and even lower abdominal strengthening may be incorporated.

- Correction of foot biomechanics – this is often done with the use of a rigid shoe inserts (softer versions are used in the elderly or in diabetics) where forefoot and rear foot pronation are corrected. This can often be done cheaply without the need of expensive podiatric orthotics. Forefoot pronation and, to a lesser degree, pes planus can be improved in mild presentations with strengthening of the tibialis posterior. This is performed whilst inhibiting the use of tibialis anterior.

Whilst these protocols are being carried out, the patient is taught how to tape their own knee. This should give complete and immediate relief of pain and allow them to maintain their work or sporting commitments until full resolution of the problem has occurred.

If you have any further questions on this subject, or you would like to contact the physiotherapist best suited to managing your problem please call or email us.

© Andrew Thompson