Chronic Compartment Syndrome

What is Compartment Syndrome – Acute and chronic?

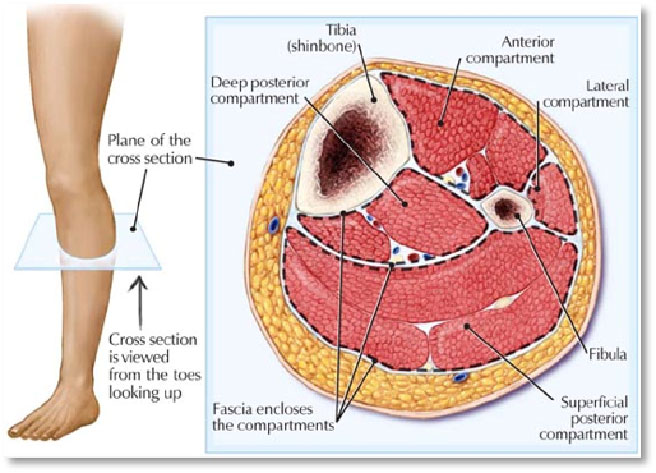

Throughout our body many muscles that have similar functions are not only close to each other anatomically but are frequently ‘bound’ within a common fascial sheath. This sheath – a thin tendon-like structure that surrounds the muscles – provides a degree of compression to these muscle groups. This enhances their contractile strength and allows for better movement between adjacent muscles or muscle groups. The term “compartment syndrome” is most commonly used to describe “acute compartment syndrome”. In this instance, trauma (often resulting in a fracture of the underlying bone and/or intrinsic damage to the soft tissues within a given compartment) results in bleeding and an increased pressure within a confined muscle compartment. This rapid build-up of pressure within the compartment is a medical emergency and can cause damage to the surrounding nerve and vascular tissue as well secondary ischaemic injury to the local and distal tissues.

Acute compartment syndrome may result from trauma to the region (sporting injuries, motor vehicle accidents etc) but may also arise following regional surgery when blood continues to leak into the compartment following surgical closure. In these situations a surgical fasciotomy is performed (cutting of the fascia that forms the compartmental sheath) in order to quickly relieve the pressure within the compartment(s).

Chronic compartment syndrome (CCS) causes a similar build-up of pressures within a given muscle compartment but instead results from the ongoing (chronic) use of a muscle (or muscle group). It is a painful condition that typically affects the calf or shin region during exercise. This article will address only chronic compartment syndrome of the calf and shin – a common physiotherapy presentation.

| The calf musculature is divided into 4 anatomical compartments – the anterior compartment and the lateral compartment are most commonly affected in CCS. The posterior deep compartment and the posterior superficial compartment are far less commonly involved. |  |

The physiological causes chronic compartment syndrome

There are 2 broad mechanisms by which chronic compartment syndrome is thought to be caused:

- The relative increase in tightness and reduction in elasticity of the surrounding fascial tissue. This is due to an increase in fascial fibroblastic activity (cellular proliferation) resulting from repeated or excessive use of a muscle. This means that the compartment is “bound” by more rigid, less elastic tissue over a period of time and although such structural tissue changes are part of the normal physiological response to muscle stress, in sufferers of CCS this cellular response may be excessive. As yet no genetic correlation has been found to predispose people with a ‘predetermined’ exaggerated fibroblastic repair response to sufferers of CCS. This would not alter the management of the condition even if such a correlation were found.

- Reduced or poor autonomic control of venous blood return. During high intensity exercise, muscles can physically expand by as much as 20%. The increased oxygen demand of a muscle during exercise results in both an increase in the amount of blood delivered TO the muscle as well as a resultant, reflexive (autonomic) response to provide sufficient venous return of blood AWAY from the muscle (back to the heart). When venous return (“drainage” of blood away from the muscle) is insufficient, pressures inside the muscle compartment continue to rise during exercise. This is an unusual theory as to why chronic compartment syndrome may occur because:

- CCS is not associated with other autonomic symptoms (altered local thermoregulatory response, hyperalgesia etc),

- because regional sympathectomy is not advocated for treatment of chronic compartment syndrome (and is unlikely to be viable to safely study in sufficient patient numbers) and

- because it does not explain the long-term conservative (non-surgical) management of patients with CCS by core, lumbo-pelvic stability programmes (discussed below) – such programmes which are effectively employed by physiotherapists to manage CCS should not (and cannot) alter regional autonomic activity.

A third, less substantiated theory, suggests that low-grade lumbar dysfunction (often with negligible or absent lumbar symptoms) may impair reflexive inhibition of antagonistic muscle action during the ‘loading response’ and ‘terminal stance’ phases of the gait/running cycle. This theory would not only explain the positive contribution that correcting foot biomechanics can make to managing CCS but also the very real association of long-term resolution of CCS with abdomino-lumbar core stability training programmes in treating this condition.

The physical/practical causes of chronic compartment syndrome

The mechanical aggravators of CCS may include:

- Abnormal foot biomechanics (such as flat or pronated feet). This significantly alters the biomechanical stresses that are placed through the foot and ankle and transmitted to the calf. Such changes in foot biomechanics can significantly alter the workload placed on each muscle compartment.

- Tightness in the posterior calf muscles (gastrocnemius and/or soleus). This can have the effect of increasing the pressures with other compartments by causing compensatory tightness and overuse.

- Sub-optimal or imbalanced exercise schedules. This can facilitate the continuation and exacerbation of compartment syndrome. Running on soft surfaces (e.g. beach running or cross-country running) and ballistic regimes (e.g. plyometrics or hypertrophy training) can trigger the onset of CCS symptoms.

- Weak hip stabilizers. In the way that abnormal foot biomechanics can have a profound affect on the overall biomechanics of the lower limb, imbalance of the pelvic musculature can facilitate the development and continuation of compartment syndrome by placing additional stress on the musculature of the calf. Such pelvic muscle imbalances are commonly seen in cyclists, dancers and gymnasts whose flexibility and hip extensor strength (excessive workload of the gluteus maximus muscle) can cause insufficient rotational or lateral lower limb stability during gait.

- Poor footwear. Shoes that do not support the arch or heel can be a significant factor in the manifestation of CCS. Having shoes that adequately support the intrinsic foot biomechanics is essential. Additional support can be provided by correct shoe-lacing techniques or orthotic support – your physiotherapist will discuss the most suitable orthotic option for your specific biomechanical needs, your footwear and your training regime. Lacing options will be explained to you by your physiotherapist and may provide additional, subtle assistance to your recovery.

How is chronic compartment syndrome diagnosed?

CCS is most accurately diagnosed with a compartmental pressure test (outlined below). Symptoms commonly described by sufferers of CCS include:

- Pain or tightness in the muscles at the front of the shin or on the side of the calf. This pain increases with exercise and resolves with rest (10 to 30 minutes). It may be associated with a feeling of ‘fullness’ in the region or altered sensation in the area around the site of pain or in the outer margins of the foot and ankle.

- A gradual worsening of symptoms over several days, weeks or months and an increase in the intensity of pain during this period or a reduction in the time before the onset of symptoms during exercise. Your physiotherapist will take a history of your symptoms and correlate this with potential differential (alternate) diagnoses – these include: shin splints (medial tibial stress syndrome – discussed on this website), tibial or fibular stress fractures, periostitis, tendonitis (achilles tendonititis/paratendontitis, tibialis posterior and tibialis anterior tendonopathy), common-peroneal nerve impingement, Osgood Schlatters Disease (discussed on this website), popliteal artery impingement syndrome and vascular claudication.

Your physiotherapist will also assess your lumbar spine, pelvis, hip and knee as potential sources for your calf pain.

If CCS is suspected your physiotherapist will recommend a “compartment pressure test”. This is performed by measuring the pressure within the affected muscle compartment following exercise. In many ways the test is similar to measuring your blood sugar levels to see if you are diabetic or pre-diabetic. To test for diabetes, blood sugar levels can be taken during non-fasting periods (random blood sugar levels), when fasted (fasting blood sugar levels) or after ingesting a glucose solution (glucose challenge test). Likewise your compartment pressures can be tested at rest, immediately after exercise or 5 minutes after exercise. (I like this comparison because many of my patients are familiar with the “glucose tolerance testing” regime.

The compartment pressure test is performed by inserting a needle into the affected compartment and measuring the pressure exerted by hydrostatic pressures arising from within the muscles at those time intervals described above. The test is considered positive if you have a pressure greater than or equal to 15 mmHg before exercise or greater than or equal to 30 mmHg one minute after exercise or greater than or equal to 20 mmHg five minutes after exercise. It is not dissimilar to measuring the pressures within your car tires by using a hand-held pressure gauge.

pressures arising from within the muscles at those time intervals described above. The test is considered positive if you have a pressure greater than or equal to 15 mmHg before exercise or greater than or equal to 30 mmHg one minute after exercise or greater than or equal to 20 mmHg five minutes after exercise. It is not dissimilar to measuring the pressures within your car tires by using a hand-held pressure gauge.

How will physiotherapy treat Chronic Compartment Syndrome?

Once a definitive diagnosis is made your physiotherapist will aim to correct any excessive biomechanical stresses placed through your lower limb. This will involve assessing your gait pattern, your running style, your footwear as well as your exercise regime – insufficient rest between exercise sessions can worsen symptoms whilst certain rapid, maximal to sub-maximal training regimes can also provoke the pain of CCS during your rehabilitation.

Treatment will follow three crucial paths:

- Correction of lower limb biomechanics – this may involve prescribing orthotics, altering your footwear, lacing techniques or even developing your running style.

- Release of the affected calf muscles – this may take the form of deep-tissue massage, stretching, dry needling or procaine therapy (also called ‘wet needling’. It involves the injection of local anaesthetic into the effected muscles).

- Lumbopelvic core stability and strengthening – this is a long-term programme and can take numerous forms. Specific muscles around the lower back, pelvis and abdomen will be strengthened to facilitate support of the lumbar spine during exercise. Your physiotherapist will discuss the most appropriate retraining regime with you in order to maximize compliance. Progressing this training regime in patients with concomitant spinal issues will also be taken into consideration by your physiotherapist

Progress is commonly slow in the early stages of your rehabilitation. You may be advised to abstain from running from 2- 4 weeks before graduating your return to sport. This progressive reintroduction to physical activity needs to be carefully coordinated.

How is Chronic Compartment Syndrome managed surgically?

When conservative management fails a surgical fasciotomy (or partial fasciotomy) may be suggested. This is an operation whereby the fascial layer around the affected muscle group is cut. In years past, this would involve a rather lengthy and unsightly incision over the front, inner or outer calf. Nowadays the incision is usually no more than 5 to 7cm in length. Although considered a very safe and successful surgical procedure it (like all treatment protocols for CCS) does not guarantee full recovery of symptoms and patients may need the procedure repeated (re-released).

“The majority of patients surgically treated for CCS experience a high level of pain relief and are satisfied with the results of their operation. The level of pain relief experienced by patients is not related to the magnitude of the immediate post exercise compartment pressures. Despite the possibility that some patients have less favorable outcomes, experience complications, or need subsequent operations, fasciotomy is recommended for patients with CCS.” American Journal of Orthopaedics.

For more information on CCS or to contact the physiotherapist best suited to managing your problem please call or email us.

© Ryan Dalby, Andrew Thompson