Achilles tendonitis and enthesitis

What is tendonitis and enthesitis?

Every muscle in the body attaches to a bone at both ends. However, muscle does not attach directly to bone. Instead muscle firstly attaches to tendon tissue and then the tendon attaches to the bone. Using the word “attach” is actually a little misleading. In reality the small cells of a muscle amalgamate with tendon cells at what is called the musculotendinous junction (pictured right) and at this point, the tissue is a composite of both muscle cells and tendon cells – this is a common site of muscle injury. The tendon cells then amalgamate with the bone/periosteal cells – this site of connection is called the enthesopathic junction (where the tissue is a composite of both bone and tendon).

Every muscle in the body attaches to a bone at both ends. However, muscle does not attach directly to bone. Instead muscle firstly attaches to tendon tissue and then the tendon attaches to the bone. Using the word “attach” is actually a little misleading. In reality the small cells of a muscle amalgamate with tendon cells at what is called the musculotendinous junction (pictured right) and at this point, the tissue is a composite of both muscle cells and tendon cells – this is a common site of muscle injury. The tendon cells then amalgamate with the bone/periosteal cells – this site of connection is called the enthesopathic junction (where the tissue is a composite of both bone and tendon).

In medicine the suffix “itis” is used to imply “inflammation” – appendicitis (inflammation of the appendix), meningitis (inflammation of the meninges – the lining of the central nervous system) or bronchitis (inflammation of the ‘bronchi’ – the airways that make up the lungs). Tendonitis therefore implies inflammation of the tendon tissue. The term ‘achilles tendonitis’ is generally used to describe inflammation of the tendon itself or inflammation of the sheath of tissue that surrounds the tendon (the paratendon). For purposes of this article it is unnecessary to differentiate whether the tendon and/or the paratendon is involved as the physiotherapy treatment for both is almost identical.

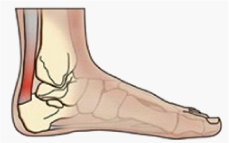

Enthesitis therefore can be thought of as inflammation at the enthesopathic junction (the site of bone and tendon union). In normal situations the enthesopathic junction a very small region of tissue and is defined using microscopy. It is only when we see enthesopathic inflammation that this region may become visible and osseous (bony) change may even show up on x-ray.

What is achilles tendonitis?

Problems with the achilles tendon can spell disaster for the athlete. Tendonitis can be very slow and frustrating to treat. Many doctors and physiotherapists believe that the only thing to truly cure achilles tendonitis is death. This may sound rather bleak but in reality there may be some truth to the statement. Many of the treatments for achilles tendonitis aim to allow the patient to return to their previous level of activity without pain. However it is not uncommon to find that when the person is required to work a little harder – they have a busy few weeks of training or they are pushed that little bit further in their sport or at work – the achilles inflammation returns. So before we get too depressed with the outlook, let’s discuss some basics.

Problems with the achilles tendon can spell disaster for the athlete. Tendonitis can be very slow and frustrating to treat. Many doctors and physiotherapists believe that the only thing to truly cure achilles tendonitis is death. This may sound rather bleak but in reality there may be some truth to the statement. Many of the treatments for achilles tendonitis aim to allow the patient to return to their previous level of activity without pain. However it is not uncommon to find that when the person is required to work a little harder – they have a busy few weeks of training or they are pushed that little bit further in their sport or at work – the achilles inflammation returns. So before we get too depressed with the outlook, let’s discuss some basics.

The achilles tendon is the large cord-like structure at the back of the heel. It connects the calf muscles (gastrocnemius and soleus) to the heel bone (calcaneum). It is an engineer’s nightmare – not only does it take the entire force of the body during walking or running (in fact it is required to withstand 4 to 5 times the weight of a person during activities like jumping or sprinting) but it has an extremely poor blood supply. Hence when the achilles tendon sustains an injury (this may be the small micro-trauma that results from prolonged or repetitive use of the tendon or more substantial tendon tearing as a result of rapid, resisted calf muscle contraction) the poor blood supply to the tendon is often insufficient to produce normal tissue healing.

Hence when the achilles tendon sustains an injury (this may be the small micro-trauma that results from prolonged or repetitive use of the tendon or more substantial tendon tearing as a result of rapid, resisted calf muscle contraction) the poor blood supply to the tendon is often insufficient to produce normal tissue healing.

Achilles tendonitis may be acute (developing over several days) or chronic (developing and persisting over several weeks or months). The pain of acute achilles tendonitis may actually ease as the player begins to play sport. Resting the injury will relieve the pain but often the tenderness persists. Whist there is any tenderness remaining, it is very likely that the pain will eventually return with activity. Chronic tendonitis (which often follows on from untreated acute tendonitis) produces a more constant pain during activity. Often there is thickening or local swelling of the tendon.

The causes of achilles tendonitis and enthesitis

Several factors can contribute to the development of achilles tendonitis. These include:

- Wearing high-heeled shoes that shorten and tighten the calf muscle

- A sudden increase in the amount of training or walking

- Poor footwear that rub against the tendon or do not support the foot adequately

- Training on hard or uneven surfaces – beach running and running up hills is notorious for this

- Insufficient stretching or recovery between training sessions

- Poor foot biomechanics – excessive pronation is the most common

- Weight gain

What does physiotherapy do to treat achilles tendonitis and enthesitis?

When you make an appointment to see a physiotherapist, COME PREPARED. It is preferable if someone else can accompany you to the appointment – they can be shown ways in which they can help to hasten your recovery at home and reduce your physiotherapy costs. You will also be given an enormous amount of information whilst you are being treated. This is a good time to have someone else ask questions and listen to the answers for you. If achilles problems are not treated appropriately the first time, they become increasingly difficult to treat in the future and can cause permanent lifestyle limitation.

Your physiotherapist will assess your footwear and your activity level (both at work and during sport). They will then assess you ankle, calf and foot to see is any biomechanical or pathological conditions exist concurrently that may be contributing to excessive workload of the achilles tendon.

Your physiotherapist will exclude other differential diagnoses including retro-calcaneal bursitis, arthritis, peroneal tendonitis, tibialis posterior tendonitis and achilles tearing (the treatment of which is considerably different to that of tendonitis).

Treatment then follows three paths:

Treatment then follows three paths:

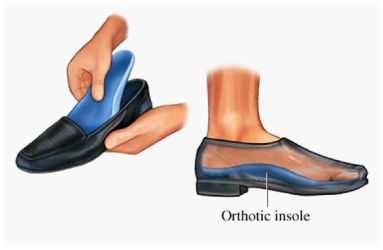

- Correction of foot biomechanics – advice on footwear and/or the prescription of orthotics.

- Loosening of muscle and joint structures that may be impairing or altering normal movement of the calf muscles and ankle joint. This may include mobilising or manipulating the bones of the ankle and the foot as well as stretching and releasing the muscles of the calf.

- Restrengthening – this is usually done initially as an eccentric strengthening programme which progresses to include isometric, concentric and finally ballistic movements of the ankle.

You will be taught how to stretch and massage your calf muscles at home as well as how to massage the tendon itself – this can be a tricky part of the programme and needs to be demonstrated by a trained professional as it is easy to aggravate the local inflammation if it is done excessively or in the wrong manner.

You may also be advised to rest the injury and on how to graduate your return to sporting activities. Often taping or bracing the ankle or the achilles itself can be extremely helpful. There are numerous taping and bracing options available and these need to be directed by your physiotherapist depending on the sports you play, the site of the inflammation and the pathology of the injury (is there thickening of the tendon, involvement of the paratendon etc).

You will be required to adhere to a very strict home exercise programme for at least 4 to 6 weeks. Your strengthening programme will continue for up to 6 months but this is less regimented than the initial intervention which is designed to settle the pain and inflammation of the tendon.

Other treatment options for treating tendonitis and enthesitis

The use of non-steroidal ant inflammatory medications can greatly assist the progress of treatment. Your doctor may also suggest a corticosteroid injection to the achilles. This often gives very good relief of symptoms in a much shorter time frame but it remains essential that you continue a stretching and strengthening programme for the following 2 to 3 months so the inflammation does not reoccur.

Prolotherapy can be used to manage enthesitis – an irritant (usually a dextrose solution or even the patient’s own blood) is injected into the tissue causing a proliferation of fibrous tissue (‘prolotherapy’ = proliferation + therapy). Both enthesitis and chronic tendonitis can be treated using ‘extracorporeal shockwave therapy’ though this is often used as a last resort because of the expense involved.

If you have any further questions on this subject, or you would like to contact the physiotherapist best suited to managing your problem please call or email us.

© Andrew Thompson