Disc herniation/bulge/prolapse

(Disc herniations, bulges and prolapses)

Lumbar pain arising from injury to the intervertebral disc is by far the most common presentation of lower back pain seen in a physiotherapy clinic. It is also one of the most commonly misdiagnosed spinal conditions. Many diagnosticians still believe that radicular (referred) pain must accompany all discogenic presentations. This is not the case.

Many health professionals will only conclude a problem is discogenic (arising from the intervertebral disc) if the patient has severe pain and limitation of movement or presents with a ‘list’ – a temporary and acute lateral flexion of the spine (not dissimilar to the appearance of a scoliosis). Again, this is not always the case. In more subtle presentations, patients may be told that their problem is “muscular”. This is often partially correct as the source of much of their pain does arise for the surrounding myofascial structures, but this is seldom the primary cause of their symptoms.

What causes a disc bulge?

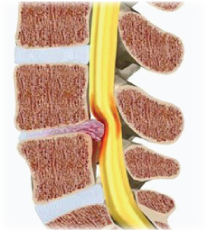

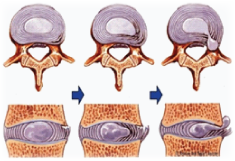

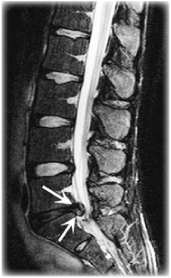

Disc bulges arise when cumulative trauma (usually over many years and arguably commencing in childhood) causes the inner, ‘soft’ centre of the intervertebral disc (the nucleus pulposus) to protrude through its surrounding cartilage tissue (the “annulus fibrosis”). It is when this protruding inner-disc material causes irritation of surrounding tissues (either by direct compression of a structure or by subsequent inflammation) that pain arises (see picture opposite).

There are two common clinical presentations of disc bulge:

- acute/traumatic and

- delayed inflammatory onset.

Acute disc bulges, (also known as ‘sudden onset’ or ‘traumatic’ disc injuries) are the type most readily diagnosed correctly. They are perhaps the stereotypical presentation of back pain. Patients will present after an acute and sudden onset of pain and often describe having moved into lumbar flexion (bending forward) and rotation (twisting) when they first noticed their initial symptoms. Many patients will describe having lifted something at the time, although this is not always the case. These patients more commonly present with a list and marked limitation in most lumbar movements. They will describe the typical compressive aggravations of disc herniations – pain with coughing, sneezing, sit to standing etc. Many will have no radicular symptoms and such patients generally take longer to respond to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication and physiotherapy. Such patients will nearly always describe a significant history of ‘minor’ back problems in the past or indeed may have experienced identical symptoms with a previous episode of back pain.

Delayed inflammatory onset disc pathologies are by far the most common lumbar presentations and are commonly misdiagnosed. Patients will present with more diffuse pain, gradual onset of symptoms (with generally no obvious causative event) and more frequently (though by no means always) will have some radicular referral into the bottom muscles or leg. Many presentations of “sciatica” are examples of this. They generally have less limitation of movement and will often describe “waking up” with their symptoms having gone to bed the night before relatively pain free. On questioning they may describe having done some unaccustomed form of physical activity the day prior to the onset of their symptoms – an unusually long spell in the garden or a day spent moving furniture. It is these patients that are often told their problem is “muscular”.

Another common misconception with discogenic pain is that if no evidence of nerve root compromise exists on CT or MR imaging then there must be an alternate diagnosis to explain the patient’s symptoms. It is important to remember that many patients with lumbar disc injuries will have no evidence of nerve root compression when imaged. (A very obvious and dramatic L5/S1 disc herniation is pictured opposite)

Physical assessment

Generally speaking, those patients that present with acute onset of pain and a list are assumed to be discogenic and are treated as such until their acute symptoms subside and a more thorough physical assessment can be done. Their movements are often limited in all directions but particularly in extension (the patient will often present in a flexed standing posture) and lateral flexion away from the list (as if trying to correct the lateral curvature of the spine).

If assessable (and the severity of pain may prevent this being performed on the initial consultation) a patient may have a positive ‘straight leg raise’ or ‘prone knee bend’ (depending on the level of disc involvement) – these are tests that will be carried out by your doctor or physiotherapist during the assessment. Coughing and sneezing will often sharply aggravate symptoms as will weight bearing on the contralateral side to which they are listing (if the patient is listing to the right, left leg weight bearing is likely to aggravate their pain). Assessing deep tendon reflexes, proprioception, power and sensation can provide considerable information about the severity of any underlying nerve impingement – pain alone is not always a true indicator of severity. Urinary habits, erectile dysfunction and signs of cauda equina involvement are routinely questioned.

In patients with the more common, delayed inflammatory presentation, a full assessment is usually much easier and more practical. The physiotherapist will assess the patient’s movement into flexion, extension and side flexion. They will also assess combinations of these movements to exclude other common underlying pathologies.

Finally each segment of the lumbar spine is assessed for symmetry of movement and resistance to passive ranging in five planes – posterior to anterior (PA), left and right rotation, left and right lateral flexion. Each vertebra (or those suspected to be involved) need to be localised and assessed for movement in relation to the levels both above and below them – i.e. in isolation. This has no huge influence on the diagnosis (a thorough history and physical assessment will have given the likely diagnosis long before now) but allows the physiotherapist to formulate a treatment plan. It will help to dictate what manual techniques are used, in which position the patient needs to be placed during treatment and the force to use when applying such interventions.

As a footnote to the above paragraph, it is vital that patients with discogenic pain are not manipulated (forcefully thrust or “cracked”). This is a very common cause of iatrogenic disc prolapse and often regresses a very treatable patient to one that requires surgery.

Treatment

Acute symptoms, are treated with gentle oscillatory mobilisations usually in prone (if not too painful for the patient) or supine. Advice at this time is aimed at relative rest (preferably supine with knees flexed – pictured opposite) and anti-inflammatory modalities – medications, heat and analgesia. Patients may also be advised to sleep in this position with the knees supported by pillows for 1 or 2 days whilst their acute symptoms subside. At this time ice may also be of some help to relieve pain but this is really the only situation where ice is used in the management of spinal injuries. There are arguments that can be made for either ice or heat during this initial 48 hour period so use whatever modality provides you with relief. Beyond this time however, heat is always preferred.

Once the severe pain and irritability has settled the treatment of these two ‘types’ of disc patient now become more congruent. Patients may be treated with mobilisations (oscillations) as well as McKenzie or Mulligan ‘mobility interventions’. Throughout this period patients continue to be advised to avoid or minimise their time spent in a seated position – driving, computer work etc. Where this cannot be avoided, adequate chair support, good posture and regular breaks to stand and move around are encouraged.

It is now that direct muscular release techniques can be applied safely to the patients. This may involve deep massage, stretching or dry needling (a technique not dissimilar in effect to Procaine therapy where local areas of muscular tightness or knots are pierced by a sterile acupuncture needle or a syringe). Prior to this time, releasing of muscular support (prematurely) can worsen the symptoms considerably. In the acute period, the spine becomes dependant on the muscular spasm that has been ‘generated’ for some degree of support. It is debatable therefore if muscle relaxants are detrimental to recovery during this time. Arguably they may allow a patient to rest more comfortably if they have the luxury of being able to take time off work, but physiologically they are of much more benefit once this acute period has passed.

Subsequent treatments focus on mobilisations (oscillatory movements of the spinal segments) specific to what limitation of movement exists. It is at this time that prolonged sitting often remains arduous and for this, a combination of mobilisations and traction are of great benefit. Often lumbar taping will be applied to limit flexion and support the spine when sitting. Complete resolution of symptoms can take between 1 and 4 weeks and although this can seem a very slow and inconvenient rehabilitation, it is a considerable improvement to the recommended 8 to 12 weeks that is usually seen when patients rely on medication alone.

Finally, patients are advised on the ways in which they can prevent this problem from reoccurring. Specific lumbar extension mobility programmes are often initiated, as well as core-strengthening regimes. Physiotherapists are well versed in discussing other risk reduction methods such as ergonomics, weight loss and correct lifting and manual handling techniques.

If you have any further questions on this subject, or you would like to contact the physiotherapist best suited to managing your problem please call or email us.

© Andrew Thompson