Scheuermann’s Disease

What is Scheuermann’s disease?

Scheuermann’s disease (also known as Sherman’s Disease, Scheuermann’s kyphosis, Calvé disease and Juvenile Osteochondrosis of the spine) is a spinal condition of childhood resulting in the improper development and wedging of the vertebral bodies. It is a self limiting disorder (meaning it will not progress once skeletal maturity is reached in the adolescent) and is named after Danish surgeon Holger Werfel Scheuermann.

How is Scheuermann’s disease diagnosed?

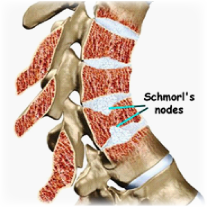

The diagnosis is made if there is wedging of the vertebral bodies, narrowing of the intervertebral disc space, Schmorl’s nodes (protrusions of the cartilage of the intervertebral disc through the vertebral body endplate and into the adjacent vertebra), and kyphotic deformity (a ‘hunched back’ appearance). On x-ray, small changes may be seen in the growing parts of several vertebral segments. These changes may progress throughout a child’s growth and predispose the lower thoracic spine to degenerative changes later in life.

What are the symptoms of Scheuerman’s disease?

Although the condition has an ominous sounding name, it is not necessarily a problematic disorder. Mild cases of Scheuermann’s disease are often completely asymptomatic and may only be incidentally diagnosed. Shcheuermann’s disease occurs in adolescent children and is relatively common – quoted in some studies as occurring in 25% of all children to varying degrees. The condition usually becomes apparent in early or mid adolescence with the advent of some forwardly flexed (round shouldered) deformity. It can be accompanied by backache and stiffness and this is often made worse by sitting.

During the onset of Scheuermann’s disease, the child’s posture often changes. The normal back curvatures may become exaggerated and the child is often told by his parents and teachers not to slouch. The backache can be in the middle and lower parts of the spine and both the progressive severity of spinal deformity and the associated symptoms can vary greatly from patient to patient. Symptoms of Scheuermann’s disease (if any) will generally last between 6 months and 3 years.

Once growth of the spine has finished, the progressive deformity halts and symptoms usually resolve fully.

How is Scheuermann’s disease treated?

The treatment of Scheuermann’s disease depends upon the severity of pain and the degree of mechanical change (deformity) seen on examination. The pain may become prominent during the more active adolescent growth periods of the spine and when severe, relative rest from aggravating activity is necessary. Traditionally, the deformity of Scheuermann’s disease was treated in a similar fashion to that of scoliosis (lateral deformity and rotation of the spine) – adolescents were confined to rigid spinal braces for several years at a time. Such strict correction of deformity is now seldom recommended in the management of Scheuermann’s disease and nowadays patients are instructed on exercise based regimes and lifestyle modification to minimise the progressive deformity of the spine and prevent secondary long term complications.

A physiotherapist will prescribe exercises to maintain the mobility of the spine (minimise stiffness) as well as strengthening exercises to encourage the development of postural muscles (and hence halt the progressive kyphotic deformity). Emphasis is placed on maintaining spinal rotation and extension throughout the thoracic and thoracolumbar spine. It is debatable as to whether mobilisation or manipulation of the spinal joints plays any significant role in the management of Scheuermann’s disease. There is no evidence to suggest that spinal manipulation can alter spinal deformities such as kyphosis or scoliosis though it is not uncommon to find patients who get considerable (short term) symptomatic relief with this type of treatment.

It is important that manual work to the spine be performed only by trained health professionals and that results of treatment occur rapidly – one or two treatment sessions is all that should be necessary to see results if manual therapy is to play any role at all. It is important to note that excessive and repeated spinal manipulation can lead to hypermobility and instability of the spine and this is thought to accelerate degenerative change later in life.

Your physiotherapist will also advise you on more generalised interventions to help minimise spinal stiffness and deformity. Participation in sporting activities (pain allowing) that encourage chest expansion (getting “puffed”) is recommended. Swimming is ideal but any sport that holds the attention of a teenager is suitable.

During times of increased pain (eg exam/study periods, travel or at times of skeletal growth) patients will be advised to rest from their sporting activities. Prescribed exercises (specific to the condition) can be continued during these periods and some patients will benefit from short bursts of manual treatment by a physiotherapist – massage and spinal mobilisation may provide significant relief during these times.

Finally, a physiotherapist will also discuss ergonomic interventions to aid postural support. This may include the use of ergonomically appropriate chairs when studying as well as school bags that do not accentuate forward or lateral spinal flexion.

In more severe cases where spinal deformity poses a threat to spinal cord function or where postural change inhibits normal respiratory or digestive processes, correction using surgical realignment and fixation may be necessary.

Spinal pain in children should always ring alarm bells. Persistent pain or pain that arises without any obvious causative trauma requires accurate diagnosis and appropriate management. Please feel free to call or email us if you have any questions regarding this topic. Children will always be given appointments preferentially at Kingsley Physiotherapy.

© Andrew Thompson